‘Hello I Want To Die, Please Fix Me’: a martyr in the war against mental health stigma

By Zoe Askew

Content Warning: this article discusses suicide, self-harm, depression and mental ill health in general.

Have you ever read a book and related to it so much you’ve irrationally questioned whether the author had been spying on you? Or maybe they have a magical power that enables them to read your every thought and feeling?

Perhaps you go so far as to think, for a split second, that the words stained with black ink on the pages between your fingers aren’t actually real, and you’re just in a really long, really vivid dream? Or this is it! You have finally, completely lost your mind, and this is your fabricated reality?

After reading, Hello I Want To Die, Please Fix Me, this was exactly how I felt.

Hello I Want to Die, Please Fix Me is the memoir chronicles of Canadian journalist and author Anna Mehler Paperny, who, like millions of people worldwide, battles the all-too-common, havoc-wreaking, incapacitating, stigma harbouring disease called depression.

Depression is a havoc-wreaking illness that masquerades as personal failing and hijacks your life.

Anna Meher Paperny

On a Friday afternoon in late September 2011, Anna returned home from another day working in her dream job at The Globe and Mail and attempted to end her life. Days later, she woke in the ICU, forearms secured to the steel bed railings with Velcro straps, tubes piercing her arteries, and a dialysis machine beside her head yielding systematic rhythmic noises as it churned blood in and out of her body.

Following her suicide attempt eliciting almost an entire week’s stay in the ICU, a smart, sardonic doctor propelled the 24-year-old journalist into the labyrinthine of Canada’s psychiatric care system.

It was incomprehensible to think Anna would ever come accustomed to the smell of stale piss lingering in the hospitals’ psychiatric ward hallways or the copious number of appointments with a consistent rotation of mental health professionals. Or that she would no longer be shocked when the system refused to provide care to the most vulnerable and desperate people in the community.

But she did.

And she wrote a book about it.

And it’s phenomenal.

Published in March 2020, Hello I Want To Die Please Fix Me begins with Anna Mehler Paperny’s first suicide attempt in 2011 and continues with her courageously raw and raucous account of living with depression and the assiduous desire for self-annihilation; together with an in-depth investigation into the myriad of ways professionals treat and fail to treat depression, the profoundly inadequate mental health system in Canada, the cultural and social discourse surrounding mental health illnesses, and the stigma that comes hand in hand with depression and mental illnesses; a seriously compelling element of the book which resonated with me – deeply.

It’s no surprise that my own reoccurring engagements with depression, confining me to an internal jail-cell of persistent, overwhelming sadness and self-loathing, and my desire to be a journalist, play a role in my adoration for this book and the author and why I so strongly connect with it.

Reciprocating Anna’s unvarnished honesty, I admit that I was desperately trying to claw my way out of a formidable, depressive hell hole in the months prior to reading this book.

After seeking professional help and emerging from that place of unrelenting darkness, I discovered Hello I Want To Die, Please Fix Me. Okay, so not yet entirely free from depression’s chokehold and the accompanying shitty symptoms, as it was a sleepless night, and I was scrolling through the mental-health section of an online bookstore.

I was searching for a book that would help me understand why I feel the way I feel and maybe provide some new ways to cope when the serotonin gets low and the idea of leaving my bed, let alone the house makes my stomach curdle (and more often than not, puke).

A few scrolls down, there it was. In hindsight, a significant contributing factor to my purchase of this book was the desperation to hear someone else’s experience of depression and all the misguided decisions that follow, hoping it would somehow validate my own experience and provide comfort in the fact I wasn’t alone. Depression is unfathomably lonely.

Payment accepted.

A bright yellow book with large pink and red letters arrived neatly packed in a brown cardboard box two weeks later.

From the preface, I was hooked.

The depth of depression’s debilitation and our own reprehensible failure to address it consume me because I’m there, spending days paralysed and nights wracked because my meds aren’t good enough. But this isn’t some quixotic personal project that pertains to me and no one else. Depression affects everyone on the planet, directly or indirectly, in every possible sphere.

I don’t want to be the person writing this book. Don’t want to be chewed up by despair so unremitting the only conceivable response is to write it. But I am. I write this because I need both life vest and anchor, because I need both to scream and to arm myself in the dark. Maybe you need to scream and arm yourself, too.Anna Meher Paperny

In my life, very few times has a book engrossed me on every single page and left me clinging to every sentence in anticipation of what was next. But my god, this book did just that.

In a compelling, strategically structured 337 pages, Anna Mehler Paperny provided an insight into why I feel the way I feel; through sharing her story with brave honesty, I found the consolation I was so desperately searching for.

Closing the backboard of the bright yellow book, I had learnt so much more than I had anticipated, not just about myself and depression but the entire mental health system and the magnitude of depression’s effects.

The only thing public dollars consistently pay for is crisis care – the costliness, least efficacious way to treat any kind of mental disorder. Post-crisis, post-discharge, you’re on your own, and chances are you’ll end up needing urgent intervention again shortly.

Anna Meher Paperny

The author exposes the shocking lack of funding for mental health research across all fields, from neurology and pharmaceutical to psychiatry and counselling.

It wasn’t enough for Anna to just discover that the entire mental health system is grossly underfunded, causing deeply rooted flaws in understanding, diagnosing, and treating depression.

No, she had to know why.

Employing her meticulous investigative skills, she dove further into the depths of depression, the mental health research and care system and all that it encompasses.

Bringing us to why mental health is so underfunded and my favourite aspect of the book – fucking stigma.

Yep. Stigma is a significant reason why mental health is so horribly underfunded.

And just to clarify, the lack of funds for mental health research and psychiatric care is not exclusive to Canada.

This is a global trend – Australia included.

1 in 6 Australians aged between 15 and 25 are diagnosed with depression, and since 2014 suicide has been the leading cause of death for those aged between 15 and 44.

Yet the mental health sector receives less than half the funding of physical health sectors, and stigma is to blame.

It’s messed up, right!

There are many studies and articles from across the globe that support Anna’s findings and elucidate why stigma plays a role in the lack of mental health funding, from City University of New York’s Department of the Psychology to Australia’s trusty newspaper The Guardian.

While the discussions of stigma throughout Hello I Want To Die, Please Fix Me are beneficial to anyone who reads it, for me, they were overwhelmingly pertinent and ignited a sense of empowerment. And anger but mostly empowerment. Oh, and tears. A lot of tears.

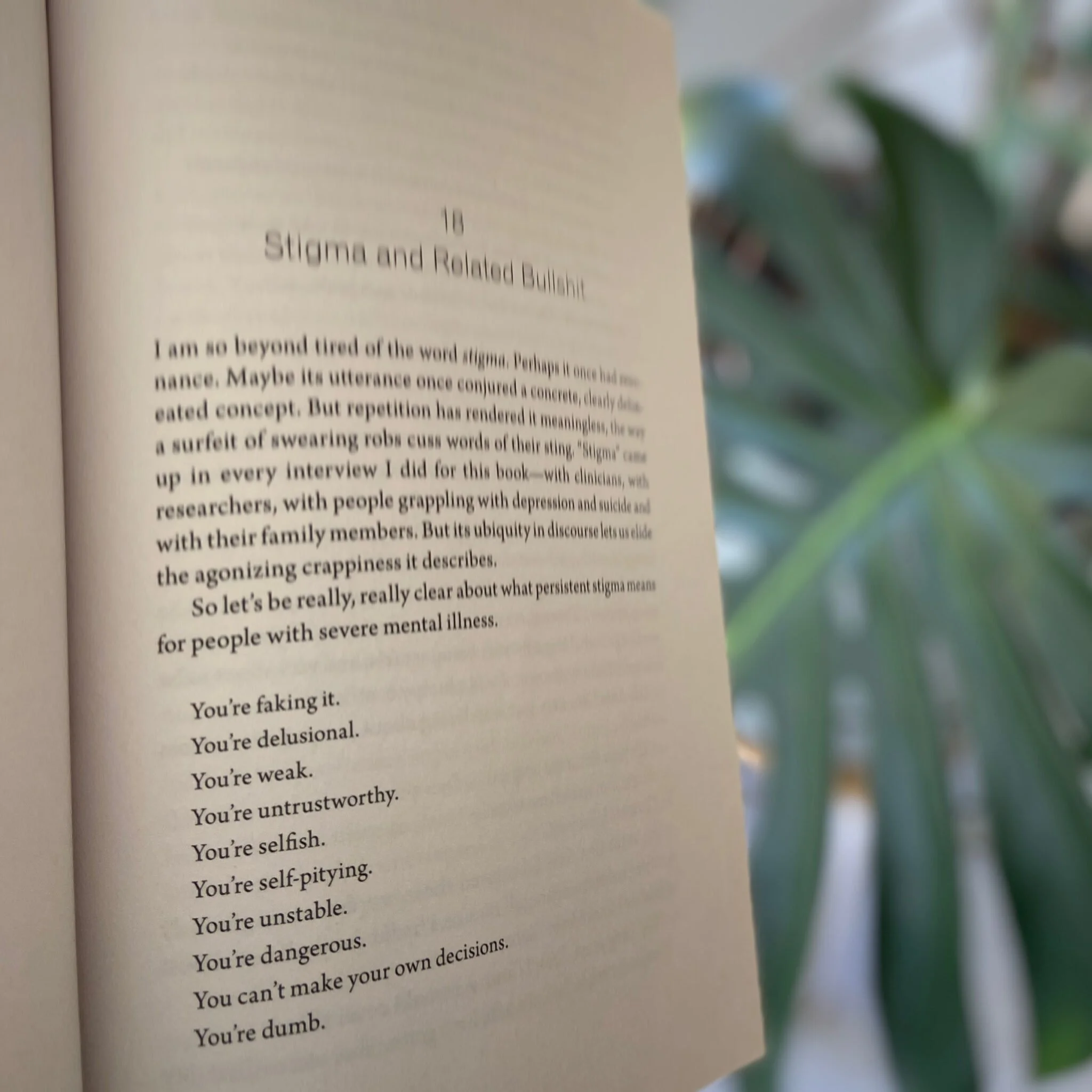

Chapter 18 is titled ‘Stigma and Related Bullshit’. Anna Mehler Paperny shares her encounters with stigma together with stories from Mary and Michelle and Micheal and Deanna.

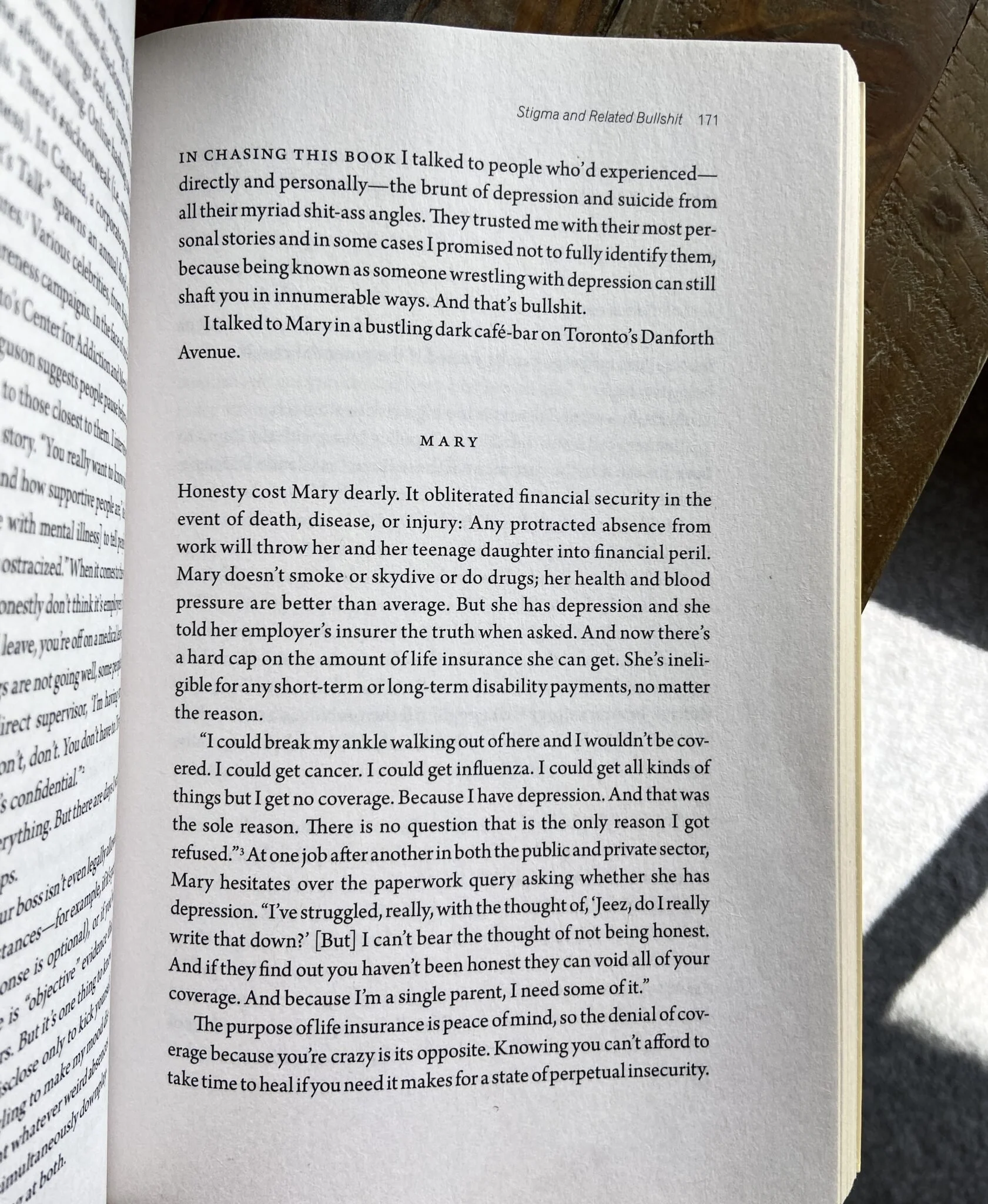

Mary

A single mother who suffers from depression. When asked by an employer’s insurer whether she had depression, Mary answered truthfully—as a result, obliterating her financial security, she was ineligible for any short-term or long-term disability payments, no matter the reason.

So when Mary started a new job, she hesitated at the spot on the paperwork; do you have depression?

In her decades living with depression, Mary built up a support network, which is vital for those suffering from mental health illnesses. However, Mary remains paralytically afraid of being seen as weak, afraid people will think differently of her.

Reading Mary’s story, every molecule of my skin rose. Every time I sit in a chair, filling out paperwork for a new job, an internal war breaks out as I deliberate whether or not to disclose my mental illness.

Because, like Mary, I, too, am petrified to be seen as weak, or unreliable, or incapable. I, like Mary, do not want to be defined by my depression.

Michelle

A college student whose family refused to acknowledge any mental pain or distress – expected to keep face by keeping silent. Despite swimming in a sea of oblivion, Michelle dragged herself out of bed and saw a therapist. She was diagnosed with depression.

“I didn’t want to admit it at first. I was like, what does that say about me? Who would want to deal with somebody who has these types of issues? I was stacking guilt on pressure on self-blame.”

Tears. I did say there were lots of tears in this chapter. Countless times, I’ve lay curled under my doona, distraught by the self-convinced fact that my depression and anxiety make me unequivocally unloveable.

Stigma’s ubiquity in discourse lets us elide the agonising crappiness it describes. It is gross and profoundly damaging.

Anna Meher Paperny

The author of, Hello I Want To Die Please Fix Me, has opened my eyes to the depths and malice control stigma has on those suffering from depression, our government, and all societies across the globe. She opened my eyes to the fact that stigma will not cease unless we start talking about mental health illnesses, really talking about it.

“For ages, the dictate has been not to write honestly about suicide—not to mention even the word, never mind methods, lest, in referencing it directly, you prompt suicidal spirals in others. But you can’t tackle the endless abyss of wanting to die on tiptoes; that just leaves you with the half-hearted interventions we’ve pretended are the best society can do. I need to be faithful to the experience. This is how I felt, and this is how I acted; this is what people in despair are driven to do. These are the people we fail in myriad ways, and this is the cost of that failure.”

Anna Meher Paperny

Anna Meher Paperny and her book have genuinely inspired and empowered me. Because despite living in a digital world where Instagram influencers, celebrities and your friends from high school routinely upload posts captioned “mental health matters” and “it’s okay not to be okay”, seldom do we really share the shit storm that is depression.

Rarely have I ever sat next to a friend, pathologically sad and in fear of my own safety, and if asked, “are you okay,” said anything other than, “I’m fine; I’m just tired”.

Hello I Want To Die, Please Fix Me is a brilliantly written, incredibly researched, shockingly informative book and a martyr in ending stigma and an illustration of how mental health issues and suicide should be discussed.

“Our failure to address this illness is a systemic fuckup with an enormous impact; it compounds marginalisations of race and income and harms most those least able to advocate for themselves. It’s inadequately explored, and conversation on the subject, as with so many systemic fuckups, is too often dominated by platitudes and siloed extremes.”

Anna Mehler Paperny

If you are struggling with your mental health or are experiencing thoughts of self-harm or suicide, please reach out.

Lifeline has qualified counsellors available 24 hours a day who you can call on 13 11 12 or chat with online.

You can also call Suicide Call Back Service on 1300 659 467, Beyond Blue on 1300 22 4636 or Mens Line Australia on 1300 789 978.

This article was originally written for publication on The Owl. For more articles written by journalism students from the University of Canberra, please visit The Owl‘s page.